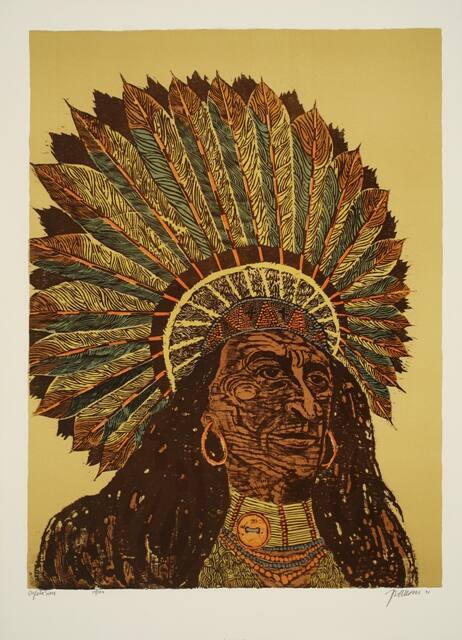

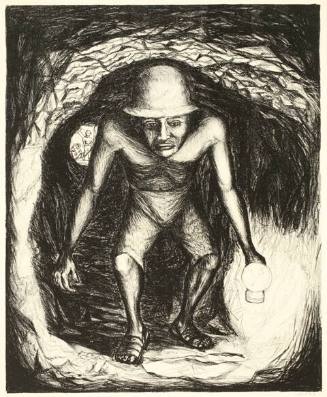

Antonio Frasconi

born Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1919; died New York, New York, 2013

In 1953, Time magazine called Antonio Frasconi America’s foremost practitioner of the ancient art of the woodcut. Four decades later, Art Journal called him the best of his generation.

Mr. Frasconi did not reach this pinnacle by adhering to orthodoxies. He found inspiration in comic books as well as the old masters. He decried art education, saying the average student does not learn the pertinent questions, much less the answers. He abhorred art that dwelt on aesthetics at the expense of social problems. He repeatedly addressed war, racism and poverty, and devoted a decade to completing a series of woodcut portraits of people who were tortured and killed under a rightist military dictatorship in his home country, Uruguay, from 1973 to 1985.

“A sort of anger builds in you, so you try to spill it back in your work,” he said in a 1994 interview with Americas, a magazine of the Organization of American States.

Mr. Frasconi, who died on Jan. 8 at 93, illustrated more than 100 books, and his work is in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the New York Public Library, the National Gallery of Art and the Smithsonian. His woodcuts appeared on album and magazine covers, holiday cards, calendars and posters, and in exhibitions around the world. Several of his children’s books won awards. In 1963 he designed a stamp to honor the centennial of the National Academy of Sciences.

In 1968 he represented Uruguay at the Venice Biennale, exhibiting prints from 20 years of work.

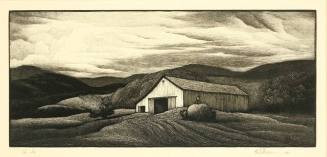

Much of that work was done in the studio at his home in Norwalk, Conn., where the views of migrating birds and passing seasons from the window influenced his art. He built the house in 1957, and his son Miguel said he died there.

Mr. Frasconi’s was patient and meticulous in his art, which involves making an impression on paper from a design carved in a block of wood. Before producing a woodcut titled “Sunrise — Fulton Fish Market” in 1953, he spent three months wandering Lower Manhattan’s wharves and the holds of fishing boats. He spent hour upon hour studying “just how a man lifts a box,” he said.

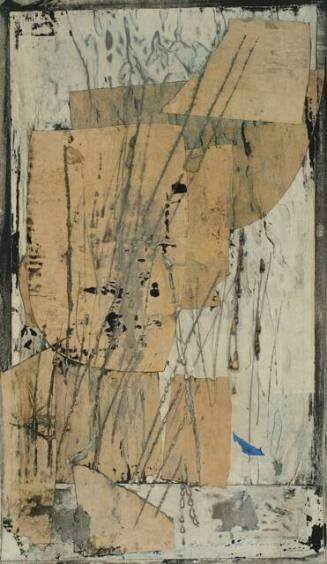

He then spent three weeks carving five wood blocks, each to apply a different color, as they are stamped successively on the same sheet of paper. He said the capricious nature of wood governed many artistic decisions. He loved the hands-on experience of working with wood, some of which he gathered from the beach in front of his home.

“Sometimes the wood gives you a break,” he told Time in 1963, “and matches your conception of the way it is grained. But often you must surrender to the grain, find the movement of the scene, the mood of the work, in the way the grain runs.”

Mr. Frasconi said he took up the art after being attracted to the idea of making multiple prints, in part so he could offer art to people at reasonable prices. The woodcuts of Paul Gauguin were an enormous influence, he said.

Antonio Rudolfo Frasconi was born to Italian immigrant parents on April 28, 1919, in Buenos Aires; a few weeks later his family moved to Uruguay. His father was frequently unemployed, and his mother worked in a restaurant and as a seamstress. He dropped out of art school at 12 because he was bored with copying from plaster casts of classical sculpture and became a printer’s apprentice. On his own, he made posters deriding Franco and Hitler, which he signed “Chico.”

In 1945 he came to New York on a one-year scholarship to the Art Students League, and the next year he had a show at the Brooklyn Museum. After moving to California, he worked as a gardener and as a guard at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, where he had an exhibition.

Returning to New York, he collaborated with the adapter Glenway Wescott and the book designer Joseph Blumenthal on “12 Fables of Aesop,” which was published by the Museum of Modern Art and honored by the American Institute of Graphic Arts as one of the year’s 50 best books. He illustrated a poem by Federico García Lorca on the brutality of Franco’s police.

A later political work about the Vietnam War superimposed bombsights on terror-stricken peasants. He illustrated selections from the poems of Herman Melville to comment on the Ohio National Guard’s killing of students at Kent State University in 1970.

For many years Mr. Frasconi, a citizen of both Uruguay and the United States, taught at Purchase College of the State University of New York.

His first marriage, to Rene Farmer, ended in divorce. His second wife, Leona Pierce, a noted woodcut artist, died in 2002 after 50 years of marriage. In addition to his son Miguel, Mr. Frasconi is survived by another son, Pablo, and a granddaughter.

Some of Mr. Frasconi’s work was devilishly playful. His 1952 book, “The World Upside Down,” pictured a bull butchering a human, a man in a bird cage while a bird cavorts outside, and a sheep herding a flock of humans. A dog sleeps in bed, while a man slumbers in a doghouse on the floor. A fire hydrant is nearby, apparently in case the man needs it.

Person TypeIndividual

Terms

- Buenos Aires

- New York

born Dracut, Massachusetts, 1889; died New London, Connecticut, 1971

born San Francisco, California, 1902; died Fort Bragg, California, 2000

born Chicago, Illinois, 1922; died Lombard, Illinois, 2012

born Cedar Rapids, Iowa, 1903; died Eugene, Oregon, 1981

born Michoacán, Mexico, 1922; died Cuernavaca, Mexico, 2002

born Edo, Japan, 1798 ; died Japan, 1861

born Sowan, Korea, 1929; died Boise, Idaho, 2009

born Tappan, New York, 1840; died Brookline, Massachusetts, 1922

born Paris, France, 1898; died Honolulu, Hawaii, 1979

born Paris, France, 1813; died Paris, France, 1894